So Not Hollywood

An integrated arts response to

Jill's narrative for the Women & Meth project

About the series. . .

Often, when doing interpretive artwork, I take basic themes, forms, and medium from initial thoughts that float up while I’m reading through the narrative for the first time. For this series, the phrase that almost immediately came to me was: That’s just so Hollywood…. On the surface Jill’s narrative has some of the same elements used by the movie and media industry to ‘sex up’ a story and sell theater tickets - guns, violence, drugs, money, and intrigue. But, when it comes to women, their families, and meth addiction, the representations sold by the movie industry in film are never the whole story and living meth addiction is not that glamorous.

This poetry and poster series chronicles the deeper issues in Jill’s experience of addiction and her relationships, loss, leaving, and pain. The poetry is taken directly from the interview narratives, edited into poetic form, and are considered participant-voiced works, each paired with an interpretive poster (Prendergast, 2009). A few of the posters are plays – visual and narrative - on actual films such as Home Alone (1990), Romancing the Stone (1984), and Scar Face (1982) that were popular during the 1980s & 1990s. Coincidentally, during that same time, use of stimulants -cocaine, crack, crystal, amphetamine, and methamphetamine - peaked in the U.S. (SAMSHA, 1999) as did the rise and dominance of Mexican drug cartel trafficking (Beittel, 2013). The posters are not meant to be sarcastic or a parody. Rather, the works are a deliberate overstatement - juxtaposed and exaggerated representations - of how Jill’s full experience is just so not Hollywood, when explored in depth and with compassion.

Each of the 10 posters has similar design elements. The movie credits are made up of the Women & Meth research collaborators, literally giving credit to the whole research team for the project (Washington State University School of Nursing, 2014). The graphics and font type were chosen based on the themes or events depicted in the poster and the type of movie represented, such as children’s animation, action drama, horror, romance, and documentary. The “movie star” featured in the faux films, Jill Spoke is an extension of the pseudonym (Jill) used in the research interview. I chose a consistent look for Jill Spoke, often used in the film industry: pretty, white, tall, and blonde. Additionally, the movie titles and much of the poster narrative are made up of direct quotes from the interview transcripts. This trace within the artwork establishes a direct connection to Jill’s own voice present in my interpretations of her story.

Often, when doing interpretive artwork, I take basic themes, forms, and medium from initial thoughts that float up while I’m reading through the narrative for the first time. For this series, the phrase that almost immediately came to me was: That’s just so Hollywood…. On the surface Jill’s narrative has some of the same elements used by the movie and media industry to ‘sex up’ a story and sell theater tickets - guns, violence, drugs, money, and intrigue. But, when it comes to women, their families, and meth addiction, the representations sold by the movie industry in film are never the whole story and living meth addiction is not that glamorous.

This poetry and poster series chronicles the deeper issues in Jill’s experience of addiction and her relationships, loss, leaving, and pain. The poetry is taken directly from the interview narratives, edited into poetic form, and are considered participant-voiced works, each paired with an interpretive poster (Prendergast, 2009). A few of the posters are plays – visual and narrative - on actual films such as Home Alone (1990), Romancing the Stone (1984), and Scar Face (1982) that were popular during the 1980s & 1990s. Coincidentally, during that same time, use of stimulants -cocaine, crack, crystal, amphetamine, and methamphetamine - peaked in the U.S. (SAMSHA, 1999) as did the rise and dominance of Mexican drug cartel trafficking (Beittel, 2013). The posters are not meant to be sarcastic or a parody. Rather, the works are a deliberate overstatement - juxtaposed and exaggerated representations - of how Jill’s full experience is just so not Hollywood, when explored in depth and with compassion.

Each of the 10 posters has similar design elements. The movie credits are made up of the Women & Meth research collaborators, literally giving credit to the whole research team for the project (Washington State University School of Nursing, 2014). The graphics and font type were chosen based on the themes or events depicted in the poster and the type of movie represented, such as children’s animation, action drama, horror, romance, and documentary. The “movie star” featured in the faux films, Jill Spoke is an extension of the pseudonym (Jill) used in the research interview. I chose a consistent look for Jill Spoke, often used in the film industry: pretty, white, tall, and blonde. Additionally, the movie titles and much of the poster narrative are made up of direct quotes from the interview transcripts. This trace within the artwork establishes a direct connection to Jill’s own voice present in my interpretations of her story.

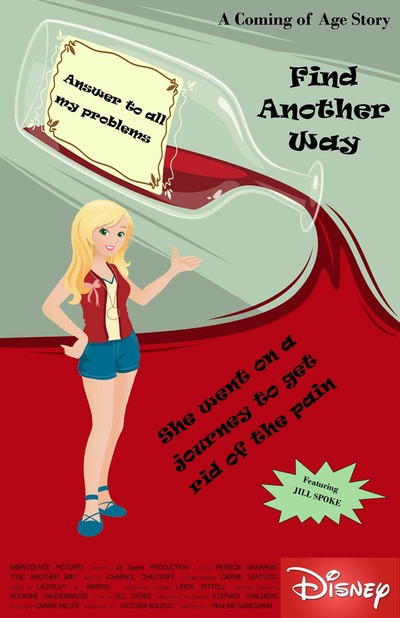

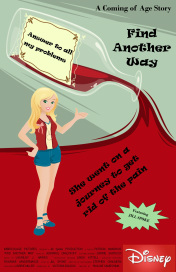

Find Another Way (11x17, digital image on paper)

This first piece depicts the beginning of Jill’s substance abuse and addiction process at age 10. The first experience she has with alcohol is striking. Though her response appears illogical, there is a rationale that is quite reasonable to her young mind. Despite the nausea, vomiting, and loss of consciousness, Jill desires to “get more” and have the control to take away her pain. Even at the beginning of her substance use, there isn’t any of the fun or relaxation, usually associated with having a drink. Using is about trying to be pain free, to feel in control. Somewhat understandably, most popular children’s films don’t explore this wounded interior, the headwaters of addiction.

This first piece depicts the beginning of Jill’s substance abuse and addiction process at age 10. The first experience she has with alcohol is striking. Though her response appears illogical, there is a rationale that is quite reasonable to her young mind. Despite the nausea, vomiting, and loss of consciousness, Jill desires to “get more” and have the control to take away her pain. Even at the beginning of her substance use, there isn’t any of the fun or relaxation, usually associated with having a drink. Using is about trying to be pain free, to feel in control. Somewhat understandably, most popular children’s films don’t explore this wounded interior, the headwaters of addiction.

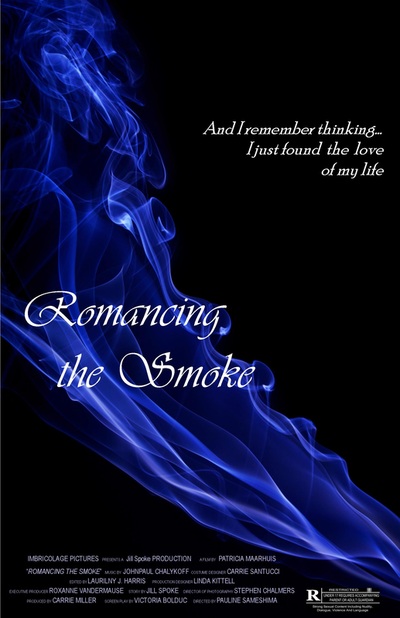

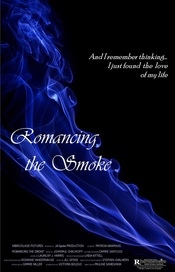

Romancing the Smoke (11x17, digital image on paper)

The second piece portrays Jill’s first use of meth and its intense emotional quality. Often, her descriptions of meth addiction and struggle toward recovery are characterized as being in an intense emotional relationship with an entity - a type of being, rather than an object or a substance. Similarly, through my experience in working with people who are addicted, I have heard clients refer to the powerful connection or even love that they felt when first using and being around others that use. Like the trope played out in the film Romancing the Stone (1984), this poster points to the “mis-matched couple on a romantic adventure”, but without the happy ending. Later on, her feeling shifts to horror, as illustrated in the piece, The Crystal.

The second piece portrays Jill’s first use of meth and its intense emotional quality. Often, her descriptions of meth addiction and struggle toward recovery are characterized as being in an intense emotional relationship with an entity - a type of being, rather than an object or a substance. Similarly, through my experience in working with people who are addicted, I have heard clients refer to the powerful connection or even love that they felt when first using and being around others that use. Like the trope played out in the film Romancing the Stone (1984), this poster points to the “mis-matched couple on a romantic adventure”, but without the happy ending. Later on, her feeling shifts to horror, as illustrated in the piece, The Crystal.

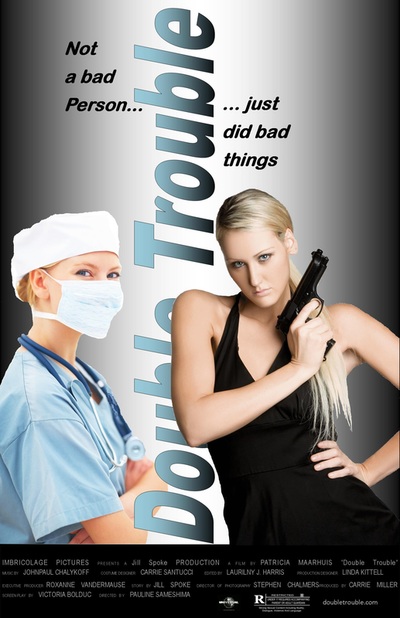

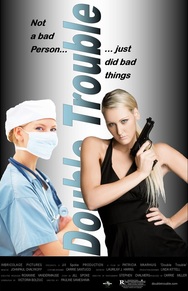

Double Trouble (11x17, digital image on paper)

This third poster characterizes the short time in Jill’s life when she is transitioning from a quickly disintegrating family and professional life to the chaos of dealing and deeper addiction. Again using a familiar metaphor, Jill has a secret double life, concealed from those around her. She works in health care ‘by day’ but deals drugs ‘by night’ but meth is quickly encroaching on every aspect of her life. Few of the harsh consequences of meth addiction have set in yet and dealing for the Mexican Mafia feels powerful and exciting.

This third poster characterizes the short time in Jill’s life when she is transitioning from a quickly disintegrating family and professional life to the chaos of dealing and deeper addiction. Again using a familiar metaphor, Jill has a secret double life, concealed from those around her. She works in health care ‘by day’ but deals drugs ‘by night’ but meth is quickly encroaching on every aspect of her life. Few of the harsh consequences of meth addiction have set in yet and dealing for the Mexican Mafia feels powerful and exciting.

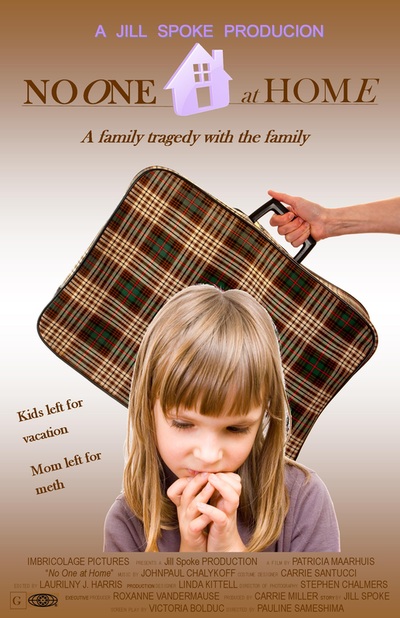

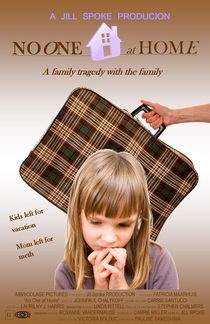

No One at Home (11 x 17, digital image on paper)

The fourth poster is one of the first pieces completed in the series but one of the most difficult to create. It is a takeoff on the movie, Home Alone (1990), a comedy which plays on every parent’s fear of accidently forgetting their child somewhere. In this case, however, it’s the children, who leave on vacation and the mom, who purposely moves out before they return. In the juxtaposed telling I, like Jill, struggled with separating out the harmful and traumatizing actions of addiction from the person who commits them.

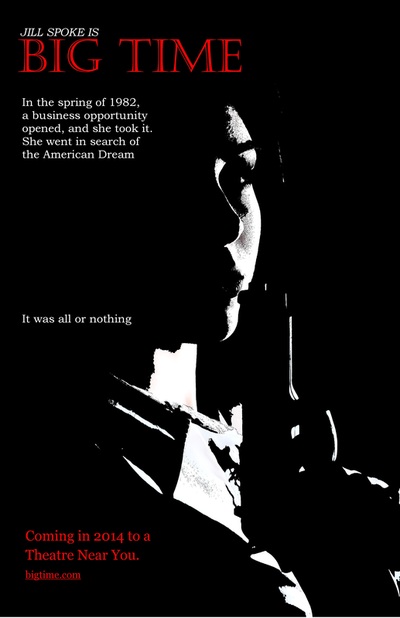

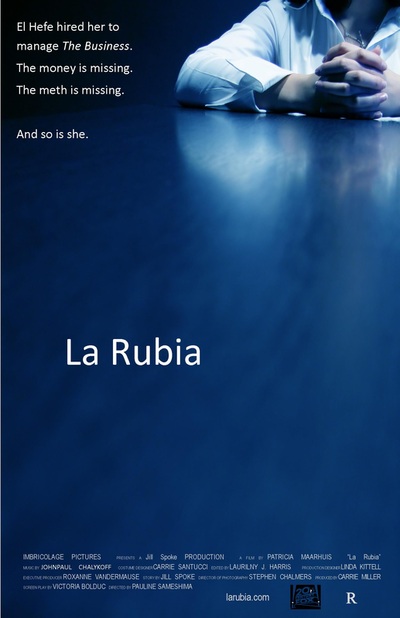

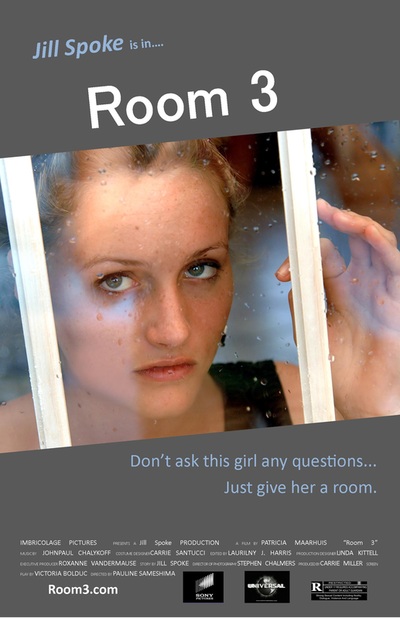

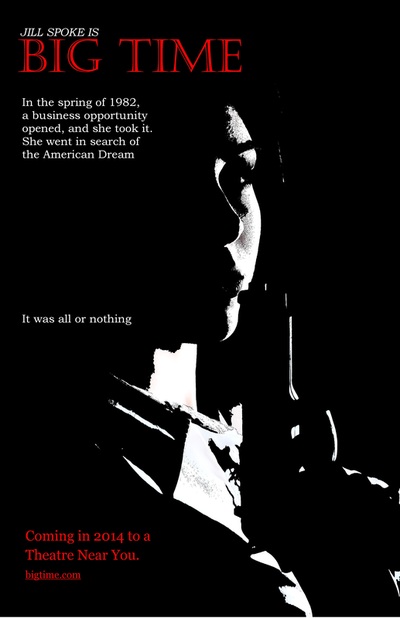

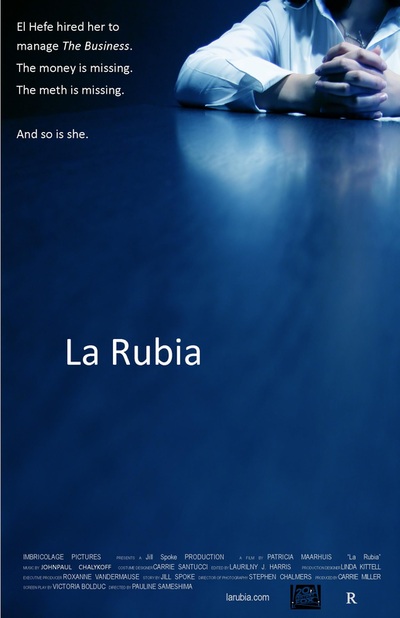

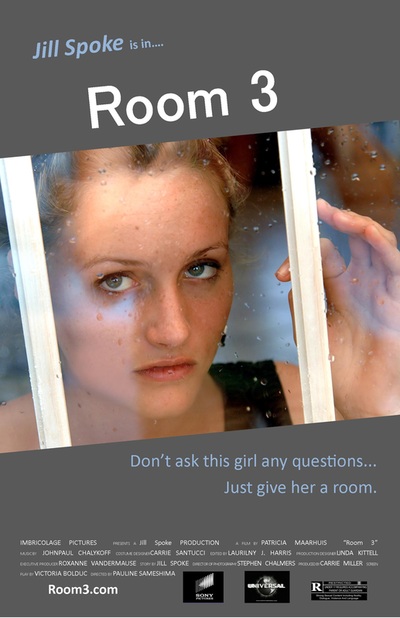

Big Time La

Rubia Room 3

(11 x 17, digital images on paper)

This trilogy of posters portrays Jill’s rise as a successful dealer, then her sudden fall from power, and the fast escape from the Mexican Mafia. Big Time is a takeoff on the movie Scar Face (1982) in its cold calculating drive for power and money. “A Big Timer” is how Jill’s children, with misguided admiration, describe her life as a dealer. La Rubia focuses on the intrigue of her set-up and betrayal by her running partner and the need to go escape. Hiding in Room 3, Jill slowly shifts from plotting murder and revenge to realizing what her life has become. Through kindness of many -the hotel manager to strangers to homeless shelter staff - she slowly approaches recovery. Often, in popular culture media, this is when the heroic story of dealing, addiction, and redemption comes to a hopeful conclusion, leaving the audience to assume the perpetual American notion of having “a happy fresh start and new beginning”.

(11 x 17, digital images on paper)

This trilogy of posters portrays Jill’s rise as a successful dealer, then her sudden fall from power, and the fast escape from the Mexican Mafia. Big Time is a takeoff on the movie Scar Face (1982) in its cold calculating drive for power and money. “A Big Timer” is how Jill’s children, with misguided admiration, describe her life as a dealer. La Rubia focuses on the intrigue of her set-up and betrayal by her running partner and the need to go escape. Hiding in Room 3, Jill slowly shifts from plotting murder and revenge to realizing what her life has become. Through kindness of many -the hotel manager to strangers to homeless shelter staff - she slowly approaches recovery. Often, in popular culture media, this is when the heroic story of dealing, addiction, and redemption comes to a hopeful conclusion, leaving the audience to assume the perpetual American notion of having “a happy fresh start and new beginning”.

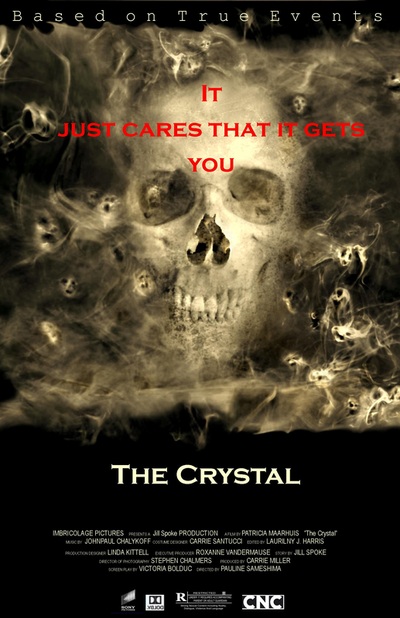

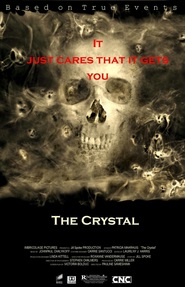

The Crystal (11 x 17, digital image on paper)

Strangely, both addiction and recovery are about loss. The eighth work in the series addresses the haunting depth of loss in Jill’s life: her children and family, a good job and home, her physical and mental health, the love of the first high, her rich and fast-paced life of dealing. As she begins her recovery, the realization of these losses starts to pile up. Like in Romancing the Smoke, Jill feels intense emotion, but this time it is anger and horror. Meth has betrayed her! After giving everything, the love of her life ends up turning on her. The addiction and loss is so deep, Jill can only describe it as something outside of herself - a rapacious evil entity that takes everything and wants more.

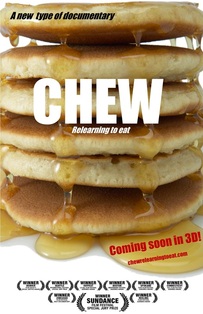

Chew (11x17, digital image on paper)

The work, CHEW – a documentary film, points to the need to relearn many of the most basic functions of life during Jill’s recovery from meth addiction. This is one of the most poignant points in her story. Jill has been entirely consumed – in body, heart, and mind – by meth use and, consequently, can’t take in enough sustenance. This description opens up the experience of recovery from meth addiction through an everyday experience – eating breakfast. Most people can fully relate to Jill’s fully embodied experience: a steaming plate of war pancakes, feeling hunger and wanting to eat. Then, there is the sorrow and the realization of an emaciated and broken condition. But next, there comes the kind touch of another wanting to care and the awkwardness of relearning a basic human function - chewing.

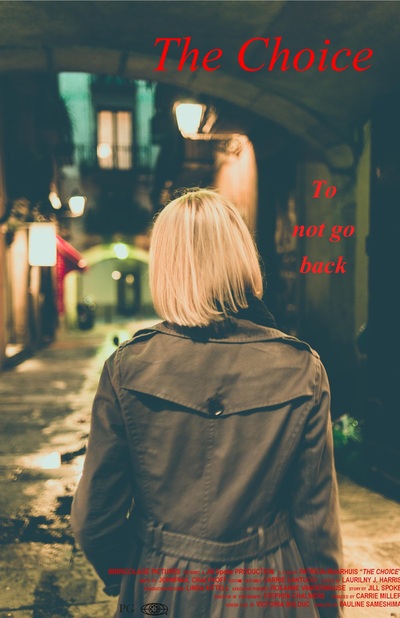

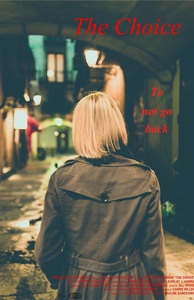

The Choice (11 x 17, digital image on paper)

The tenth piece in the series, The Choice, captures Jill’s sense of recovery. Unlike the finality of a typically happy and heroic ending, the series closes with an image that has a perennial feeling of recurrent choice. Jill speaks on a number of occasions in the interviews about what she feels her choices -or the lack of choices - are in addiction and recovery. And, Jill is clear: if she could, she would use meth but, then, addiction would completely take over and her ability to choose would be gone. Then again, once fully into her recovery, Jill feels she does have an active choice to practice recovery and to not relapse, but with ever-present vigilance.